The stately homes of England were being closed down or sold: the cruel toll of super-taxation

“This will catch ————-,” said Sir William Harcourt in 1894, when, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, his devastating measure revolutionising death duties passed its third reading. The name he mentioned was that of a big landed proprietor whom he detested.

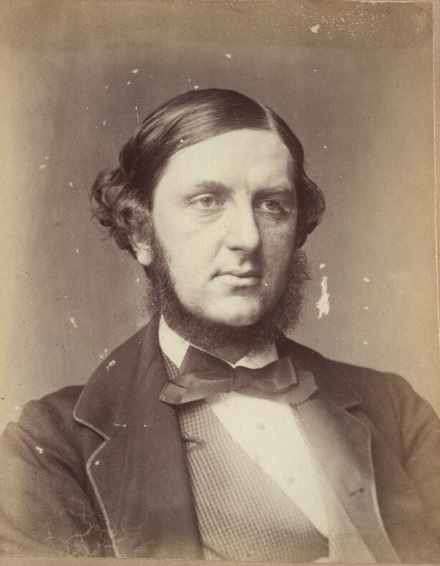

Sir William Harcourt (1827-1904) was a solicitor, journalist, politician and cabinet member in five British Liberal Governments, who in 1894 had achieved a major reform in death duties.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer, he introduced estate duty, a tax on the capital value of land, in a bid to raise money to pay off a £4 million government deficit. The imposed graduated tax on the total estate of a deceased person was capable of producing much more revenue than taxes only on the amounts inherited by beneficiaries.

The new death duties were passed despite the opposition of many, including William Gladstone and the 5th Earl of Rosebery, who believed that easily increased taxes would encourage frivolous Government spending. Other opponents regarded the tax as an attack on the great hereditary landowners.

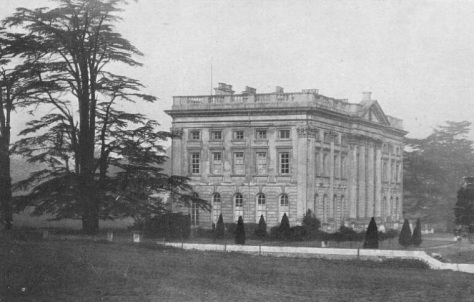

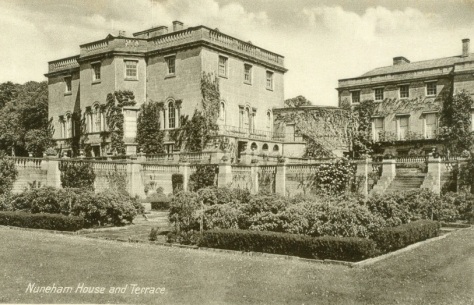

By a rare instance of poetic Justice Sir William himself was one of the earliest to suffer under an Act which increased death duties according to the degree of relationship. He succeeded unexpectedly to Nuneham, the Harcourt family place near Oxford, and was taxed heavily by his own clauses concerning inheritance from kinsmen.

It was a contentious act that impacted on the nation’s country houses throughout the opening years of the 20th century.

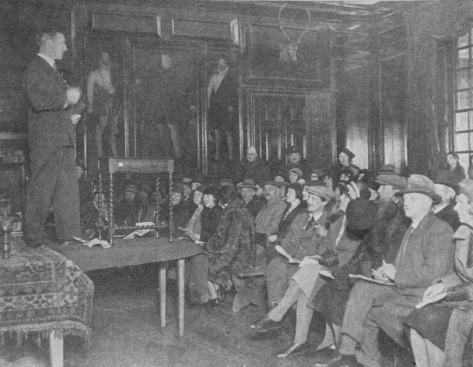

However, it took a few years before the long-term implications for landowners were realised. The Sphere, ‘an illustrated newspaper for the home’, had been founded in 1900 by Clement Shorter, who also founded The Tatler in the following year. In 1931, it highlighted the problems created by Sir William Harcourt’s act:

“The confiscation of capital – glossed under the name of ‘capital levy’ – has become the thickest plank in the Socialist and Communist platform. It has also become the practice in countries wherever the opportunity has offered. But in England – the monarchical and democratic – this confiscation has been going on steadily ever since the passing of Sir William’s Act. Later legislation has added burdens both to land and capital, with the result that the ultimate burden is becoming too heavy to be borne, and whole estates, or parts of estates, have to be sold merely to meet the death duties. However, the process may be disguised under ‘duties,’ the fact remains that men have to pay fortunes to the State simply because they have inherited money or its equivalent in land. Actually, the confiscation of capital. And that capital is used year after year as part of the national income.”

It wasn’t only The Sphere that voiced opinion. George Holt Thomas’ The Bystander was equally opposed to death duties:

“The landed classes are, in fact, being taxed out of existence under our very noses and before our very eyes. It is one of the most dramatic and cruel episodes in the whole of England’s chequered career, and most people who should know better talk like the Socialists and say that it is all for the public good. They forget that England became what she is as a result of the feudal system and that the feudal system is the best possible thing for the countryside. Time and time again in the past great landlords used to remit the rent to their tenants if it was a bad year. They were able to see that tenants got proper attention if they were ill. In fact, they looked after them. Today there is no one to do that. There is no doubt about it that the politicians have got the country into such a position that there is practically no chance for any great estate to survive financially the death of two consecutive heads of the family. It might be possible if there were a couple of very long minorities. But that is the only hope. In fifty years’ time who can say with any assurance if a single one of the great houses will still be in private hands?”

There could, said The Sphere, be only one result – the sale or closing of big country houses, with the consequent loss to local employment, tradespeople, charitable subscriptions, cutting down pensions to old servants, probably the raising of cottage and farm rents; in short, the withdrawal of one of the biggest influences in the English countryside, especially strong where the landowners have realised their responsibilities.

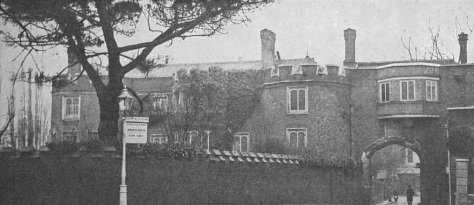

The newspaper’s response came after news from Lullingstone Castle at Eynsford, in Kent, where the Hart Dykes had lived in unbroken succession for five hundred years, a house famous for its hospitality and kindliness. The new baronet, Sir Oswald, had been obliged to close the house because, not only had he paid the duties upon his father’s death, but also on the reversion of his elder brother, on whom it was entailed, and had died in the late Sir William’s lifetime.

Lord Durham, too, had to close Lambton Castle, near Durham, having had to pay something like half a million in duties owing to the successive deaths of his father and uncle. If the late Lord Durham had lived a little while longer the duties would have been three-quarters of a million.

Sir Oswald Hart Dyke hoped to return to Lullingstone ten years later, but the Duke of Newcastle, closing Clumber House, after succeeding his brother, could entertain no hope so definite, and had lent some of the best pictures in the house to the Nottingham Museum. (Clumber House was demolished seven years later).

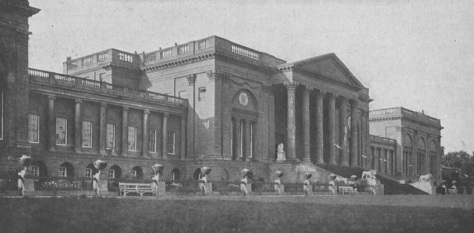

The Duke of Leeds wasn’t even fortunate enough to be able to close Hornby Castle and wait for better times. It had been demolished and the materials sold piecemeal. Stowe House, in Buckinghamshire, which Lady Kinloss had inherited from her father, the last Duke of Buckingham, had become a public school. Moor Park, at Rickmansworth, formerly belonging to Lord Ebury, was a country club. Ashridge Park, the old Brownlow property at Berkhamsted, had to be sold, and had been bought as a memorial to Mr Bonar Law, and was a training college for Conservative workers.

And the list went on. According to The Sphere, “these instances are repeated all over the country.”

The Duke of Portland had already expressed doubt, publicly, whether his heir would be able to live at Welbeck. There were rumours, too, that two big ducal castles, one in the north and the other in the south, may have to be closed, and the announcement had just been made that Lord Derby wished to dispose of his London home in Stratford Place.

Another sign of the pressure of taxation was the coming to market of The Old Palace at Richmond, the homes of Kings and Queens from the time of Henry I to Queen Charlotte, and where Queen Elizabeth died. For many years it had been the scene of delightful parties given by Mr Middleton, who had done much for its restoration. Yet other signs were Lord Harewood and Princess Mary leaving Chesterfield House, and Lady Louis Mountbatten leaving Brook House.

And Devonshire House, Grosvenor House, Dorchester House, Lansdowne House, Spencer House – where were they? Said The Sphere: “Taxation answers – flats or clubs.”

Modern inheritance tax still dates back to William Harcourt’s intervention in 1894. Today, inheritance tax is paid if a person’s estate (their property, money and possessions) is worth more than £325,000 when they die. The rate of inheritance tax is 40% on anything above the threshold, and that rate may be reduced to 36%, if 10% or more of the estate is left to charity.