A house with a fine reputation and family links to Nostell Priory. The advent of the industrial revolution altered its history and eventual loss.

According to Eilert Ekwall, in ‘The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names’, the name of ‘Ackton’ refers to an ‘oak-tree farmstead’. This appears far-removed these days, and a far cry from those days of the Victorian industrial revolution when Ackton was at the forefront of coal production. The hamlet grew up between Wakefield and Pontefract, then in the West Riding, but it was Ackton Hall that became the focal point for the area.

The first mention of Ackton Hall appears to have been in the Featherstone Parish Register in 1570, belonging to the Frost family and later passing by marriage to the Beckwiths, who sold it in 1652 to Langdale Sutherland for a price said to be £5,000.¹

The Winn family

The mansion passed to Edward Winn, the younger son of the second baronet of Nostell Priory, binding the two country houses together. Ackton Hall passed to his heir, Thomas Winn (1714-1780), who inherited a much larger house in 1765. Thomas married Mary Duncalf, daughter of Humphrey Duncalf, in 1753, and his only child was Edmund Mark Winn (1762-1833).²

The family of Winn was descended from a cadet of the house of Gwydir, who left Wales in the sixteenth century and settled in London. The immediate ancestor of this branch was George Winn, draper to Queen Elizabeth, who had issue Edmund Winn, of Thornton Curtis in Lincolnshire, who died in 1615, having married Mary, daughter of Rowland Berkeley of Worcester, sister to Sir Robert Berkeley, Knt, one of the Judges of the King’s Bench, by whom he had three sons.

George Winn, the eldest son and heir, whose residence was at Nostell Priory, was created a baronet by King Charles II in 1660. The title passed down the line until Sir Rowland Winn, High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1799, who died unmarried in 1803. The title was then devolved upon his cousin, Edmund Mark Winn of Ackton Hall.³

History portrays Sir Edmund Mark Winn as “a truly worthy country gentleman, with all the politeness of the ancient school, and all the consideration of the kind landlord.” ⁴ He died unmarried in 1833 and Ackton Hall passed to his niece, Mary, eldest daughter of Colonel Duroune of the Coldstream Guards.

She had married Arthur Heywood (1786-1851), the son of Benjamin Heywood of Stanley Hall, in 1825. The Heywood family were descended from Nathaniel Heywood who settled in Drogheda. He had three sons, Arthur, Benjamin and Nathaniel, who all returned to England.

Arthur Heywood Snr, settled at Liverpool and, with his brother Benjamin, founded a bank, Heywood and Co, and by his second wife Hannah, daughter of Richard Milnes of Wakefield, a principal member of a distinguished Non-Conforming family, had four sons, two of whom settled at Liverpool and two at Wakefield. Neither of the Liverpool sons had children, but Benjamin Heywood of Stanley Hall left a son, Arthur Heywood, who became Mary’s husband.⁵

The death of Arthur Heywood in 1851 was arguably the end for Ackton Hall as a rural mansion. His widow, Mary, remained until her death at Great Malvern in 1863. The estate was put up for sale and the sale catalogue describes the hall as an attractive stone built mansion on a moderate scale seated on a hillside and surrounded by a richly wooded and undulating country.

“Extending on the south and east is a tract of rich park-like land studded with noble oak and other trees of large growth and great beauty. The lawn and pleasure grounds slope gently to the south-west and are well-arranged with retired shrubbery and shaded walks embracing extensive views over luxuriant meadows and a magnificent country.

“In the ground floor are the entrance hall, inner hall, dining, drawing and morning rooms, and a library. On the first floor are a drawing-room and two large bedrooms, and on the second floor are another five bedrooms and three servants’ rooms. There are two water closets. Outside is a stable yard with accommodation for ten horses, a double coach house, a dovecote and farm buildings for the 42 acre farm. There are two kitchen gardens, a conservatory and a vinery, and the hall also has its own spring water supply.”¹

Despite the best efforts of the sales catalogue to find an occupant there was no chance that the hall was going to retain its charm.

George Bradley and the price of coal

The surrounding area was now ripe for industrialisation, and coal was the valued prize for ambitious entrepreneurs. The Ackton Hall estate was bought by George Bradley, of the Castleford firm of Bradley and Sons, Solicitors, who had seen the potential for exploiting the mineral assets of the land. It is suggested that he bought the hall and estate in 1865 for £23,400, with another £20,300 used to buy additional land. The cash was borrowed from the University Life Assurance Society, a transaction he would later regret.

Before arriving at Ackton Hall he had been living with his father at Leeds. He was admitted as a solicitor in 1853, but his practice had gradually dwindled due to falling business. As well as the Ackton Hall estate, he later purchased freehold land in Essex, Suffolk, Lincolnshire, Rutland and Yorkshire.

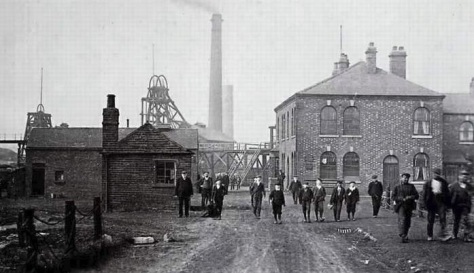

Initially, George Bradley leased Ackton Hall land to John Shaw†, who opened a colliery called Featherstone Main that soon became the largest pit in England. Encouraged by Shaw’s success, Bradley sank two of his own shafts to the Stanley Main Seam and opened his own colliery called Featherstone Manor. It was later extended to the Warren House Seam and at its peak was extracting about 200 tons each day.⁶

“The next and future returns cannot fail to give a much larger quantity, seeing that several very important estates with large areas of coal are now being opened out.” Sheffield Independent. 2 April 1870.

However, George Bradley’s coal-mining aspirations were hindered by lack of finance. In 1888, his dream ended when a writ was issued by the High Sheriff of Yorkshire on Ackton Hall. Bradley had been living in the mansion, but mounting debts were leading him into trouble. His miners hadn’t been paid, he had defaulted on payment of rates and more importantly, he was behind on mortgage payments.

Samuel Cunliffe Lister, Lord Masham

In the summer of 1890, it was rumoured that Messrs Lister and Co, of Manningham Mills, near Bradford, had purchased the Ackton Hall estate, including the Manor Colliery, adjoining Featherstone Station on the Wakefield branch of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. The estate had been due to go to public auction, but the sale by private treaty was believed to have been £180,000.⁷

In the end, it turned out that the estate had been bought in a private capacity by Samuel Cunliffe Lister, and not on behalf of the shareholders of the company. He had bought the greater part of the estate, about 1,200 acres, and carried with it all the mineral rights. George Bradley could remain at Ackton Hall and kept some adjoining land, but the mineral rights right under the house had been acquired by Mr Lister. According to the Yorkshire Post, the output from the Ackton Colliery had been comparatively small owing to the want of development, but now that the property had come into the hands of a man of such well-known enterprise and energy as Mr Cunliffe Lister, a guarantee was at once forthcoming that a great change in this respect would shortly take place.”⁸

Samuel Cunliffe Lister was one of the largest landowners in the North Riding, and in the previous nine years had expanded upwards of three-quarters of a million in purchasing the Swinton Park estate, near Masham, from the heirs of Mrs Danby-Vernon-Harcourt, Jervaulx Abbey from Lord Ailesbury’s trustees, and the Middleham Castle property, which he had bought a few months previous.

In time, George Bradley moved to Rectory House in Castleford and was declared bankrupt in 1897. The following year, the conveyance for Ackton Hall passed to Mr Middleton of Leeds, a transaction that was later brought before West Riding magistrates. In January 1906, four Leeds men were charged with having stolen a quantity of lead from Ackton Hall. It was also stated that the defendants had also engaged in removing furniture from the mansion. Thomas Middleton, a Leeds jeweller, told the court that he and his brother were the owners of the hall as trustees under their father’s will. Middleton stated that the defendants did not have permission to remove the lead. However, the case was most unusual due to the fact he claimed George Bradley had never asserted that he had a right to live at the hall, neither did he set up a right to the property. He said his father had taken possession of Ackton Hall after advancing George Bradley money. The case of theft was dropped due to insufficient evidence, but the affairs of George Bradley appeared ever more curious.⁹

The acquisition of Ackton Hall by Samuel Cunliffe Lister (1815-1906) was purely for commercial reasons. He was a rich man, born at Calverley Hall, the son of Ellis Cunliffe Lister-Kaye, who had assumed the name of Lister on taking possession of the Manningham estate, near Bradford, under the will of Mr Samuel Lister of Manningham Mill.

He was one of the greatest Victorian industrialists, a man who went against his family’s wishes to enter the church and started out in the counting house of Messrs Sands, Turner and Co in Liverpool.

On attaining his majority, young Lister prevailed upon his eldest brother to enter the worsted spinning and manufacturing business at Manningham, where their father erected a mill for them. It was here that the attention of the future was directed to the problem of machine wool combing, which at that time was in the embryonic stage. Failures to construct an efficient machine wool-comb had been so numerous that any idea of an invention capable of supplanting the labours of hand-combers was regarded as a major obstacle.

Samuel Cunliffe Lister, however, was of a different opinion, and, finding that a machine upon which an inventor named Donisthorpe was working, although at the time in a very imperfect state, gave the greatest promise of success, he bought the machine for a good round sum, and then taking Mr Donisthorpe into partnership, set himself to work out the idea of the apparatus. In this task the partners succeeded after years of labour and the expenditure of many thousands of pounds. The success of the invention practically placed the wool-combing industry for a time in Mr Cunliffe Lister’s own hands, although to begin with he had to encounter litigation in connection with his patents.

This was typical of the man and during his lifetime patented over a hundred inventions which revolutionised the silk and wool trade; to carry out his ideas, he spent a fortune of £600,000 and was more than once on the brink of ruin. In due course, however, the patents brought in a great financial harvest, and for some years before the Manningham Mills were floated as a company, the average net profit was £2 million a year.

Few men lived a life of steadier application to business, and on one occasion he publicly stated that for twenty-five years, he was never in bed later than five o’clock in the morning.

It was characteristic of the man that he should not care for public honours, and probably none of his intimate acquaintances were surprised when he declined to accept a baronetcy on the Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1877. The Peerage was not conferred until 1891, when the veteran inventor was in his seventy-sixth year.¹⁰

In addition to investing large sums in landed property, the new Lord Masham successfully turned his attention to the working of collieries. He ploughed significant amounts of money into Ackton Hall Colliery and it soon became one of the most successful pits in the country. He began to provide social facilities and housing for the miners, and the new town of Featherstone was developed in the field between Ackton and Purston as a mining town with good quality housing and social services.¹¹

However, in this industry he had an unfortunate experience with his workpeople, and it was remembered that in the dispute in the coal trade in 1893 the military fired on rioters who were destroying property at the Ackton Pit Colliery.*

Decline and fall

The rise of Ackton Hall Colliery also led to the demise of the mansion. Its proximity to the workings rendered it undesirable, the views obscured by the workings, and it was eventually split into flats. The new town of Featherstone quickly developed in the field between Ackton and Purston but, by 1969, the mansion had become so dilapidated that it had to be demolished.¹²

Ackton Colliery was the first pit to close following the end of the 1984-1985 national miners’ strike.

Notes: –

† John Shaw (1843-1911), of Welburn Hall, Kirby Moorside, colliery proprietor, chairman of the South Kirkby, Featherstone, and Hemsworth collieries. Three times unsuccessful Conservative candidate for Pontefract, who died in 1911, only son of George Shaw of Brook Leys, Sheffield.

He went to Featherstone with his father in 1866, to open out the coal field. Subsequently the South Kirkby collieries were acquired, and in 1906 the Hemsworth collieries were added. The company became known as South Kirkby, Featherstone and Hemsworth Collieries Ltd. For some time, he lived at Newland Hall, near Normanton, but soon after he removed to Darrington Hall where he remained until about 1896, when he went to live at Welburn.

*In July 1893, a fall in the price of coal led to owners to stockpile output and ‘lock out’ their workers. In Featherstone, workers were increasingly restless and on September 7 rumours spread that coal at Ackton Hall was being loaded onto wagons and then transported to the owner’s mill in Bradford. An angry crowd gathered outside the pit and confronted Mr Holiday (the pit manager) and a work gang that was loading the wagons. Eventually troops were called in. Three officers and 26 men arrived from the First Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment. A local magistrate, Bernard Hartley JP, read the Riot Act. When the crowd didn’t disperse the troops were ordered to fire warning shots. The second volley of shots wounded eight people, two of whom died of their injuries. As a result of the debacle the Liberal Government lost much of its working class support.

¹ The Featherstone Chronicle – A history of Featherstone, Purston and Ackton from 1086 to 1885.

² The Peerage.

³ Leeds Mercury. 13 June 1891.

⁴ Leeds Intelligencer. 22 June 1833.

⁵ ‘The Rise of the Old Dissent, Exemplified in the Life of Oliver Heywood 1630-1702’ by The Rev Joseph Hunter, F.S.A. 1842.

⁶ Featherstone’s Three Collieries.

⁷ Yorkshire Evening Press. 21 June 1890.

⁸ Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 20 August 1890.

⁹ Leeds Mercury. 13 January 1906.

¹⁰ Leeds Mercury. 3 February 1906.

¹¹ Wakefield Council. Featherstone Delivery Plan 2014-2016.

¹² ‘Lost Houses of the West Riding’ by Edward Waterson and Peter Meadows. 1998.

Further reading: –

Featherstones Three Collieries

The Featherstone Chronicle