“And to think that the sumptuous palace erected by Elizabeth’s wealthiest subject should have become the residence of a humble shepherd.”

Kirby Hall, near Gretton in Northamptonshire, was built from Barnack stone between 1570-1575, for Sir Humphrey Stafford, whose motto, ‘Je seray loyal,’ and the date 1572, were to be seen over the porch of the great hall, and on some of the panels of the parapet one noted the inscription, ‘Hum Fre Sta fard.’

It had one-time represented the high-water mark of Renaissance building, before it degenerated into heaviness and over ornamentation. The original plan is preserved in the Soane Museum, and the architect John Thorpe, very thoughtfully entitled it, ‘Kerby whereof I layd ye first stone Ad. 1570.’ It was so ambitious in concept that it took five years to build, somewhat too long for its owner, Sir Humphry Stafford, who died just before it was ready for occupation. His son, who probably considered the whole scheme unnecessary as they already had a fine house at Blatherwick, only five miles away, at once sold Kirby Hall to Sir Christopher Hatton, so that the only connection with the Staffords was found in the crest and badge carved in stone and wood.

It was never certain whether Sir Christopher Hatton found time to live in Kirby Hall, for he owned many fine properties, besides having to attend the Queen at Court. He didn’t go near it for five years after the purchase, because he wrote to a friend in 1580 that he was going ‘to view my house at Kirby which I have never yet surveyed.’ Sir Christopher, who was well-known to be the favourite of Queen Elizabeth, was said by his enemies to have entered Court ‘by the galliard,’ referring to the famous occasion when he caught the notice of the Queen at a masked ball by the beauty and agility of his dancing. Favours were heaped upon him, even to the apparent absurdity of making him Lord Chancellor, but in the end the Queen tired of her devoted admirer and was cruel enough to insist upon the return of a Crown debt, money which had been advanced to pay for some of the fine furnishings of the house. This was said to have broken his heart, because he died shortly afterwards.

Sir Christopher never married, but Kirby remained with his heirs. His successor, following the fashion of the day, employed Inigo Jones, the English Palladio, to re-decorate the exterior in 1640, and on the north side of the spacious courtyard that occupied the centre of the building, his work and that of John Thorpe was blended together into a harmonious whole. The arcade, pilasters, and cornices dated from an earlier period, and the windows, chimneys and attic storey formed part of Jones’ later embellishments. There was less trace of Inigo Jones’ handiwork on the opposite side of the courtyard, only the window over the porch and the side door being his.

The Hatton family kept Kirby Hall until 1764, when it passed to the Finch-Hattons.

Kirby Hall was abandoned in the 1800s, its owner moving to a newer and more commodious house, and it was left to solitude and destruction. Its lead was stripped from the roof, the oak wainscoting was carried off to ornament other houses in the district, and its stones were used to mend roads. In 1878 the Northampton Mercury said that the house had become a kind of quarry, from which stone could be cheaply obtained for the erection or repair of farmhouses, stables and other buildings in the vicinity and, it was whispered, that many richly sculptured slabs, the work of the most celebrated art-workmen of the Renaissance period, were to be found embedded, face inwards, in the walls of stables and labourers cottages. ‘We have seen such specimens of sixteenth century art in the possession of cottagers, who made no secret of the source from whence they had been obtained.’ The house was left to the estate shepherd who allowed his flock of sheep to wander the once grand halls.

Its last absent-owner was Murray Edward Gordon Finch-Hatton, 13th Earl of Winchilsea. When he inherited the property, his first thought had been to preserve the home of his ancestors from complete ruin, and he did what was necessary to keep Kirby from falling to pieces. It was his intention, ‘if ever his ship came in,’ to restore the property to its old splendour, using the profits from his stone quarries in Northamptonshire. But ‘man proposes, God disposes’; he was never able to carry out his dream. He died in 1898, and Edith Broughton, writing in The Sketch the following year, described the decay that had beholden Kirby Hall to her Victorian readers:

“The oak panelling has been torn from its walls; at the approach of a stranger, rats scuttle away through holes on the worm-eaten boards; and the decorations hang in festoons from the ceiling.

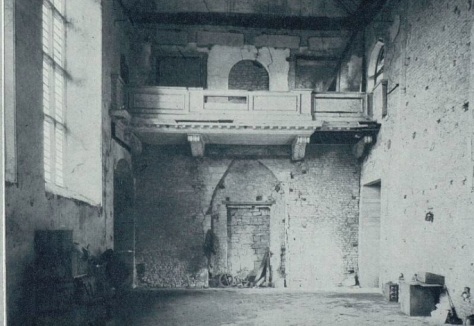

“Through the porch a short passage leads into the banqueting hall, with its musicians’ gallery, where once the soothing strains helped calm the angry passions of bygone revellers, or the merry tunes to which the light feet of the dancers in the room below kept time. Good-living, good-fellowship, good times were these; but alas for the frailty of earthly things, a change has come to this once beautiful mansion.

“The unglazed windows, the skeleton walls, the nettle-decked passages, are in strange contrast to the magnificent architecture that in many places has been spoilt by time and neglect. A few rooms in the house are still habitable, and a caretaker lives and makes tea for the curious tourist who loves to visit ‘the homes of England.’ In the large Drawing-Room, with its huge bay-windows, it isn’t an uncommon sight to see a picnic-luncheon laid out upon the floor where once spindle-legged furniture stood on which were seated the powder-headed courtiers, as they paid their addresses to the be-jewelled and be-satined damsels of long ago.”

Edith Broughton hoped that the day would soon dawn that would see men hard at work restoring this lovely specimen of the Renaissance. ‘Which it were a sin to leave longer to ruin and decay!’

That day would take a long time coming. In 1935, the ruined mansion was under the kindly protection of the Office of Works and had suffered well over a century the utter misery of neglect. With no one interested in it, or to watch over it, it had become a roofless ruin, its windows broken, more stones removed, and its beautiful interior woodwork long gone.

Kirby Hall is approached by an outer court, with fine gateways, and is enclosed by a stone balustrade, but the main structure consists of the quadrangular courtyard, surrounded by buildings like an Oxford college. The long east and west sides were occupied by a series of small apartments and connected with one another, in which the household and guests once resided, while the Great Hall was at the southern end. The exterior of Kirby Hall is described as ‘not particularly striking’; it is the richness of the detail and real beauty of the design of the inner courtyard which makes it of importance.

Today, Kirby Hall and its gardens are still owned by the Earl of Winchilsea but is managed and maintained by English Heritage. Although the vast mansion remains partly roofless, the walls show the rich decoration that proclaims its successive owners were always at the forefront of new ideas about architecture and design. The Great Hall and state rooms remain intact, refitted and redecorated to authentic 17th and 18th century specifications.

It now enjoys a new celebrity as a filming location and has appeared in Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation, Mansfield Park, A Christmas Carol for Ealing Studios in 1999, and Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story in 2005.