The Dukeries are four estates whose boundaries join and form a green and tranquil tract of Nottinghamshire which, until the Second World War, was a celebrated beauty spot.

In 1963, the writer J. Roger Baker re-visited the area for The Tatler and discovered that once more the estates were being cared for in a way which, while retaining the feeling of pre-war grandeur, was entirely consistent with the 1960s.

Fifty-five years later, with the benefit of hindsight, his work proves to be a rather rose-tinted look at four country houses. These were the ‘swinging-sixties’ after all, but life further north was a bit grim. For at least one of these properties times would get very hard indeed.

From ‘The Tatler’ – 28 August 1963:-

Today’s image of Nottinghamshire is probably one of coal-mining sons and lovers enjoying riotous Saturday nights and hung-over Sunday mornings, plus vague race-memories of Robin Hood engaging in endless television sorties with the local Sheriff. But the core of the county has always been – and remains – Sherwood Forest which once accounted for a fifth of its area. Until the 17th century this thirty-mile expanse of woodland and ling forest belonged to the Crown; the King retaining hunting rights and the great oaks were used to build ships and – it is generally believed – to supply beams for large buildings, among them St. Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1683 the Earl of Kingston formed Thoresby Park from 2,000 acres of forest land; later another 3,000 were taken for the fourth Earl of Clare’s park at Clumber and the Duke of Newcastle began building Welbeck Abbey. At nearby Worksop stood the magnificent Elizabethan manor house begun in about 1530 by the fourth Earl of Shrewsbury. This house – the most glorious in the midlands and possibly the whole north of England was burned down (at a total loss in art treasures of £100,000) in 1761. The conjunction of these four estates is dubbed the Dukeries. In the past 30 years they have probably gone through more upheaval – retrogression and subsequent redevelopment – than in the previous three hundred. I revisited the Dukeries earlier this year when the oak, lime and birch trees were just emerging into consciousness and daffodils carpeted the parklands. It is possible to travel for miles without seeing a coal mine or any other scar on the carefully manicured landscape, or any living thing apart from birds or the odd herd of deer. The perimeter of the Dukeries is dotted with unlovely mining villages and in many places spoil heaps (buckets travel along wires to tip subterranean refuse on to growing piles) and mining plant encroach within the forest itself, but the centre of the area remains unspoiled. Or, to be more precise, has regained an unspoiled appearance.

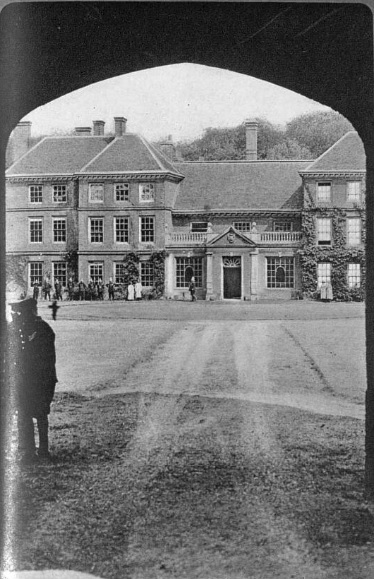

For the greatest depredations to the forests and parks happened during the Second World War when the Army took over. I remember as a small boy raiding the ammunition dumps for Very lights which enlivened the first post-war bonfire celebrations. Perhaps the worst to suffer was Clumber Park which was requisitioned as an ammunition sub depot; it had been, too, a transit camp and much of the timber felled for war purposes leaving the park in a dismal state. Clumber House itself, a basically 18th-century mansion with later enlargements, facing on to the 87-acre lake, was demolished by the Duke of Newcastle in 1937 who intended to build a smaller dwelling on a nearby site. For a variety of reasons, he never did and sold the park to the National Trust.

A miniscule remnant of the house still stands (teas are available) and the National Trust’s area agent, Mr John Trayner, has his office in the stable courtyard.

“Clumber was the hunting and farming type of park,” he told me, “and a perfect example of a landscaped 18th century park which we are slowly restoring to its original state. The forestry side is well in hand, replanting at the rate of 28 acres a year. The rest is a question of maintenance and keeping the roads and paths in trim. We are also concerned with the buildings, especially the church.”

£9,000 has been spent on restoring Clumber church which was rededicated earlier this year. “On a good summer Sunday as many as 70,000 members of the public visit Clumber,” said Mr Trayner.

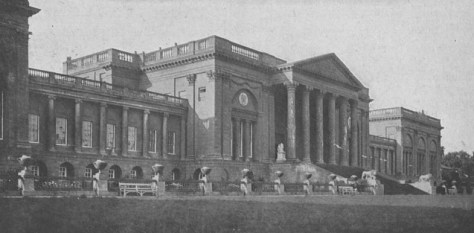

The joint estate of Thoresby is also open to the public. The hall is the home of Earl Manvers’ widow (he was the representative of the Dukes of Kingston whose title is defunct). It is not quite the Woburn of the Midlands, the Countess Manvers has made admirable use of the resources at her disposal to attract the public. In Sissons’ ‘Penny Illustrated Guide to the Dukeries’ published some 50 years ago, the rapturous author writes: ‘Everything is in the most perfect order on the Thoresby Estate and the mansion is the ideal abode of a high-minded English nobleman.

Of the estate this remains true; the park is about twelve miles in circumference, its variety of trees, lake and herds of deer (this particular estate has always retained large herds) are immaculate. Of the mansion… well, times have changed, and a few English noblemen would relish a bookstall selling Thoresby Hall place mats, waste paper bins, trays and tea towels in their great hall. The present house, another example of Victorian splendour, was designed by Salvin in 1874 and its massive, elaborate exterior confines a series of state apartments around which the public drift, open-mouthed at the fascinating collection of objets on view, ranging from the coronation robes of the Earl & Countess Manvers to some very beautiful paintings and back via a set of dolls in national costumes.

Despite the inevitable tourist attractions (did I spot a Robin Hood tea room?) Countess Manvers – an active painter, many of her works hang in Thoresby Hall – has clearly compromised with the ‘60s in the most agreeable manner, ensuring that the estate and house retain a basic feeling of a past age.

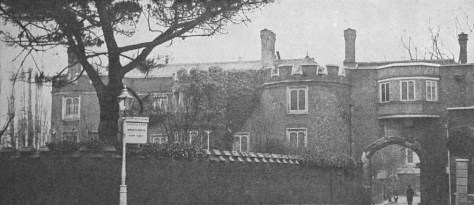

The other two ducal estates exist on a slightly different basis; to neither is the public admitted except by very special arrangement. Welbeck Abbey was first founded about 1150 but under Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries act, destroyed. The present pile – of varying periods – was begun in 1600 by the first Duke of Newcastle. The author of Sissons’ ‘Penny Guide’ goes completely berserk at the prospect of describing Welbeck, describing the wonders as ‘world-wide.’ Well. The wonders exist of a series of underground rooms and tunnels built (Sissons estimates the cost as ‘two or three millions of money’) by the fifth Duke of Portland. One is not required to indulge in a species of pot-holing to see these apartments – they are in fact just below ground level, lit by skylights.

Today Welbeck Abbey is a school – a college providing a two-year sixth-form boarding school education for boys intending to take cadetships at Sandhurst. The present Duke of Portland, who lives in a smaller house at Welbeck Woodhouse nearby, retains some state apartments for his own use.

The underground ballroom (a picture gallery originally) is now the gymnasium, and oil paintings hang on the walls, men and women of a bygone century watching lusty youths vault, practise judo and perform on parallel bars. Many of the rooms leading from the underground galleries are classrooms; football and cricket pitches are marked on the great lawns and boats sail the lake. Tactful conversion of a great home into a military college of this nature is a sure way of preserving the house from either destruction or misuse. Within the park, Welbeck village, once a completely self-contained unit, feudal in nature, serving the Abbey, retains its function; the rest of the estate is farmed by efficient and up-to-date methods.

Farming is also the function of the Worksop Manor estate which joins that of Welbeck. The manor house has been associated with various moments of history, visited by Mary Queen of Scots, by Charles I, and once tenanted by Bess of Hardwick who married the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. The present house was built by the 9th Duke after the Elizabethan house had been razed in 1761. He and the Duchess began rebuilding but the death of their heir finished their enthusiasm. The remains of their project are in a singular curtain wall attached to the main house which gives the place a strangely Mediterranean feeling; there is space, there are statues. In 1840 the manor was sold to the Duke of Newcastle of Clumber and in 1890 sold again to Sir John Robinson, passing in 1929 to his great-nephew Captain John Farr, whose widow still lives there, the 450-acre farm being managed by her son., Mr Bryan Farr, who has a house on the estate which includes 600 acres of forest land. Today Worksop Manor is probably the most striking of the four houses; with its wide courtyard and unfinished wing, completely unexpected.

And so ended J. Roger Baker’s visit to the Dukeries. But what lay ahead for these country estates? This was the 1960s, and there was still a tendency to demolish great houses that proved too costly to maintain.

Clumber Park, minus demolished mansion, became one of the National Trust’s crown jewels. Listed Grade I on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens, it has steadily been managed and maintained. It still contains the longest double avenue of lime trees in Europe, created by the 5th Duke of Newcastle in the 19th century and extending for more than two miles. The Duke of Newcastle’s study, designed by Charles Barry Jr, is all that survives of the house and is used as a café.

Worksop Manor might have been described as the finest of the four houses, but it was, and remains, the most secretive of estates. Guarded from public view, it strives to avoid publicity, the house remains in private ownership and continues to be the home to the Worksop Manor Stud.

The Dukedom of Portland became extinct following the death of Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, 9th Duke of Portland, in 1990. The military college continued at Welbeck Abbey until 2005, while Lady Anne, the unmarried elder daughter of the 7th Duke of Portland, remained at Welbeck Woodhouse until her own death in 2008. Her nephew, William Henry Marcello Parente (born 1951) inherited and moved into Welbeck Abbey making it a family home once again. The family-controlled Welbeck Estates Company and the charitable Harley foundation have converted some estate buildings to new uses. These include the Dukeries Garden Centre in the estate glasshouses, the School of Artisan Food in the former fire stables, the Harley Gallery and Foundation and the Welbeck Farm Shop in the former estate gasworks and a range of craft workshops in a former kitchen garden. The house remains private although public visits are available on a limited basis at certain times of the year.

Perhaps the most beleaguered story belonged to Thoresby Hall. To minimise the threat of coal mining subsidence the house was sold to the National Coal Board in 1979 who proposed mining underneath it. It stood empty and abandoned from 1980, and in 1983 was described ‘as gradually crumbling as a coal seam is mined under its foundations’. It was sold on the open market ten years later and after several uninspiring owners was eventually acquired by Warner Leisure Hotels. Thoresby Hall opened as a 200-room country house hotel and spa in 2000.

The writer, J. Roger Baker , was born in 1934 and studied at Nottingham University. After working at the Nottingham Evening Post, he moved to London in 1960 to take a job with The Tatler. He died in 1993.