Built: Early 1200s with later additions and extensions between 1837 and 1842. Demolished 1956

Architect: Anthony Salvin for 1837 additions

Owner: Nottinghamshire County Council

Country house ruin

Rufford Abbey had the misfortune to find its expiry date coincided with the 1950s. Had it been after the 1970s then it is likely that the house would still be standing today.

The story of Rufford turns out to be one of confusion and underhandedness.

In the end this fine house became the victim. Rufford stands among the remnants of Sherwood Forest, just two miles south of Ollerton in Nottinghamshire.

Its history is rich. As early as the 12th century it formed part of a Cistercian Abbey and estate. However, after the dissolution of the monasteries the site followed a long transition into a country house.

It fell into the hands of George Talbot, the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, famous as Bess of Hardwick’s fourth husband. If she thought she would get her hands on Rufford she was mistaken.

The house passed to Shrewsbury’s daughter, Lady Mary Talbot, in 1626, who was married to a Yorkshire baronet, Sir George Savile.

According to the writer, Robert Innes-Smith, ‘had the great-grandson of this marriage been more self-seeking and line-toeing it is certain that Rufford could have been truly one of the Dukeries’.

George Savile’s actions during the 1688 sufferings meant he would become the Marquess of Halifax and not a Duke. The title would become defunct following the death of the second Lord Halifax in 1700.

A north wing was added in 1679 and a roofed southern wing was built in the 17th century. Rufford’s ownership passed to a cousin, John, and then to another George Savile, who became the 7th Baronet.

The years that followed provided growth for the house and estate. The Bath House and Garden Pavilion were built in 1743.

In 1750 a lake was created that provided power for the new corn mill (now known as Rufford Mill). The villages of Ollerton, Broughton, Kirton and Egmanton were also added to the estate.

Following the death of the 8th Baronet in 1784 his estates were split between his niece and nephew. John Lumley took the Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire estates.

The house moved swiftly through the family and, by the 1800s, Rufford was firmly in the ascendency.

The 8th Earl employed the prominent architect, Anthony Salvin, to redevelop the house. The work, completed between 1837 and 1842, cost over £18,000. The house now contained 111 rooms, 14 bathrooms and 20 staircases. During the works a magnificent entrance avenue was created with lime trees.

The Prince of Wales became a regular visitor and used Rufford as a base when visiting Doncaster races and for shooting parties. This would continue after he became King Edward VII.

In September 1908 the King and Queen stayed at Rufford and were entertained by the Scottish entertainer Harry Lauder. During the visit the royals went on a motoring tour of the neighbouring Dukeries estates visiting Welbeck Abbey, Clumber House and Thoresby Hall but it was back to Rufford they came.

After the First World War the Rufford estate was failing.

With the death of the 3rd Lord Savile in 1931, Rufford passed to his 12-year-old son, George Halifax Lumley-Savile. His age meant that a Board of Trustees was appointed to run the estate and here began its demise.

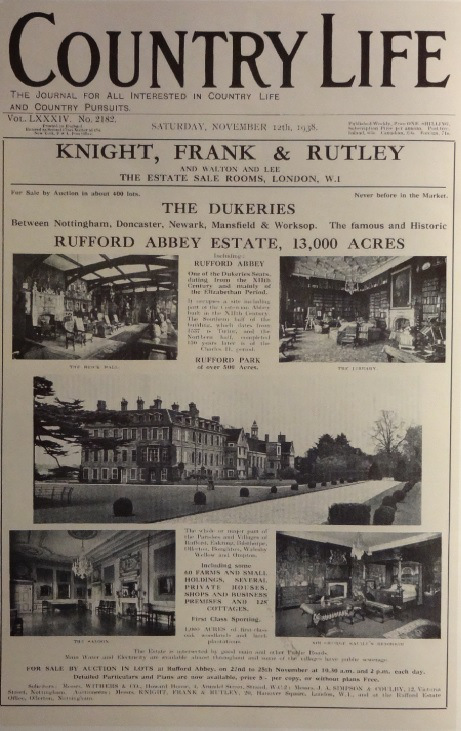

The following year the Yorkshire estates were sold to raise revenue but it took until 1938 for them to decide that Rufford was now too expensive to run. Outstanding death duties and reduced estate income meant that Rufford’s future was now perilous.

In April, Alderman Sir Albert Ball, a former Lord Mayor of Nottingham, signed a contract with Savile to buy the majority of the Rufford estate which consisted of 18,500 acres and several villages.

The sale meant that Rufford was now the fifth Nottinghamshire estate to be vacated or sold (the others were Clumber, Bestwood, Wollaton and Newstead) with the surrounding lands providing the real reasons for interest. Lord Savile would move to the family home at Gryce Hall, Shelley, in Yorkshire.

‘Sir Albert will try to sell the residence, but at the present he has no customer for it. Parts of the estate he regards as ripe for building development.’ The Times

Sir Albert Ball had originally made his fortune with the family’s plumbing business but had looked to real estate to enhance his wealth.

He had purchased Bulwell Hall in 1908 and later sold 225 acres to Nottingham Corporation.

In April 1919 he acquired the Papplewick estate in Nottinghamshire which had promptly been broken up and sold for a profit (although the house still survives today).

In 1936 he bought Upton Hall, near Newark, but his attentions appeared to wane with the purchase of Rufford which promised greater riches.

After owning Rufford for just a month Ball decided to put the estate back up for sale.

To gain the best rewards he split the estate into 400 lots. The contents of the house were the first to go and were sold at auction in the Long Gallery of the North Wing in October 1938. According to The Times this raised £25,000. There were then two further auctions – Furniture and object d’arte (raising £10,000) and a fine art sale at Christies in London which netted an additional £31,000.

The estate was auctioned in November.

The lots included farms, small holdings, 128 cottages, 6 shops, business premises and building sites within the communities of Ollerton, Eakring, Bilsthorpe, Boughton, Wellow, Ompton, Egmanton and Walesby.

Also included were 1,000 acres of prime oak woodland. The house itself was advertised as a single lot together with 843 acres of parkland. At the time the sale catalogue reported that 18,600 acres of land was for sale but Ball had already sold 7,380 acres privately.

It would take until the following summer for Ball to dispose of 14,000 acres raising £250,000. The house remained unsold and would eventually be withdrawn from sale along with surrounding land.

“Overtures are still being made for the Abbey. I don’t think for one moment that it will be pulled down. I don’t intend doing such a thing.” Sir Albert Ball

According to reports the house was being considered for conversion as an ‘educational centre’ and even as a potential holiday camp. Meanwhile, just a few miles away, quietly unnoticed, the magnificent Clumber House was demolished and lost forever.

In August 1939 The Times finally announced the sale of Rufford Abbey.

The new owner was to be Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton. This individual was the successor owner of Lytham Hall in Lancashire but resided in Jamaica. He also owned the neglected Kildalton Castle on Islay in Scotland.

According to legend he lived an extravagant lifestyle far beyond his means. He’d inherited the family fortune at 18 and subsequently plundered the Clifton estates on madcap schemes. Clifton owned a yacht, had permanent suites at The Ritz and The Dorchester and spent lavishly on racehorses.

He was at Oxford at the same time as the writer Evelyn Waugh and there is speculation that the character of Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited was based on him. He eventually managed to squander £4m and died virtually penniless in a Brighton hotel.

It is likely that Clifton’s land agent brought Rufford to his attention. He certainly had no intention of living in the house and did not appear interested in letting the property. A caretaker was left in the house but, with no maintenance since the Savile days, its upkeep was minimal.

We can only assume that the surrounding land, and its potential for development, was the real reason for Clifton’s investment.

Whatever his intentions, fate was to deal a cruel hand for both Clifton and Rufford Abbey.

While Clifton spent his days in sunnier climes he might have forgotten that there was a war on.

Within weeks Rufford was requisitioned by the War Office and would become home to the 6th Cavalry Brigade of the Leicestershire Yeomanry and the 4th Battalion of the Coldstream Guards. Churchill tanks would soon rumble over the estate and churn up the fine grassland where once King Edward VII dined on the lawns.

Large areas of surrounding woodland would be cleared for war use. Huts would be built in the parkland to the west of the house and later become temporary shelter for Italian prisoners of war.

Rufford, like many country houses, suffered at the hands of the army and its charges. One report suggested that the Italians ripped down silk brocade hangings to make into silk handbags for their girlfriends back home.

After the war Rufford was handed back to Clifton.

He received a small amount of compensation but this didn’t mean he had to spend the money on the house. He started stripping the house of its panelling and doors, almost certainly preparation for demolition. This notice came in 1949 with his agent stating“that in the current post-war economic climate it was of greater national importance to demolish and salvage valuable building materials.”

Nottinghamshire County Council refused all requests to demolish Rufford but Clifton argued that the poor state of the building meant that the surrounding land was worthless. A Building Preservation Order was served on the house but, with no solution, Clifton exercised his rights that required the enacting county council to purchase the building from him. This was probably the first such case in the country.

“It is deserted and depressing. Inside deporable apart from the twelfth-century undercroft. Nothing old left otherwise. It is suffering cruelly from dry rot to the extent that all the floors and the ground storey of the Stuart wing have been ripped up and the earth is showing through.” James Lees-Milne (June 1949)

In 1952, with the building in a poor state of repair Nottinghamshire County Council (NCC) was faced with a dilemma.

The local writer and historian Robert Innes-Smith founded the Rufford Abbey Trust with the aim of securing a viable future. However, with dry rot, rising damp, a damaged roof, mining subsidence and bulging walls, the way ahead was anything but certain.

He recently stated that the NCC seemed uninterested at the time. They might have been forgiven as they were now owners of a property they probably didn’t want.

Opinions on the future of Rufford were divided.

The Ministry of Works suggested that the mix of architectural styles meant the house was not worthy of saving. However, there were those who favoured the house to be saved. The Ministry of Town and Country Planning, the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) and the National Trust all expressed interest in its future. Indeed the National Trust had looked at Rufford as part of its Country House Scheme but decided it didn’t meet its criteria. The SPAB commissioned the architect David Nye to look at how much it would cost to make the building safe and eliminate dry rot. His suggestion was £11,745 while the Ministry of Works had suggested a figure in excess of £60,000. There were also calls from private individuals for the house to be saved.

Myles Thoroton Hilyard (from Flintham Hall), on the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, was vocal in his support, as was the Duke of Portland from nearby Welbeck Abbey. His counterpart at Thoresby, Earl Manvers, did not share his enthusiasm and suggested that Rufford ‘might not be worthy for saving’.

The records of the NCC show that 27 uses were proposed for the house.

There was interest from the National Coal Board, the British Sugar Corporation, Sheffield Regional Health Board, the County Museum and the Raleigh Bicycle Company.

Probably the most serious intention came from the Boots Pure Drug Company who proposed using Rufford as a Pharmacy College and Warehouse.

In the end there wasn’t a viable use for the building. It is likely that a report issued by the National Coal Board in 1953 had already sealed its fate. In this document they stated their intention to resume coal extraction on the western side of Rufford’s buildings that would last between 1958 and 1980 and that “extensive damage could be experienced due to possible ‘erratic subsidence’”.

In June 1956 the NCC started demolition. The work was completed in three phases. The upper floors of the 18th century east wing were removed leaving protection to the listed lower medieval undercroft while the northern Georgian extension was flattened and grassed over. (The work was steady but actually didn’t get fully completed until the late 1980s). In 1969 the remains of Rufford and its grounds were designated a country park.

Today the surviving fabric of the house is mainly Jacobean with ornate steps, porch and Anthony Salvin’s clock tower cupola. This wing was renovated for NCC office accommodation in 1998 and the Victorian kitchen developed as the Savile Restaurant. The surviving Grade II listed stables had already been converted into a craft centre with gift and craft shops.

There is at least still something for the country house researcher to see. It stands as a ‘managed ruin’ and numbers suggest it is enjoyed by many visitors.

However, you cannot fail to feel sadness and one wonders whether modern-day revenue streams might be greater had the house remained.

The timing of Rufford’s apocalypse was unfortunate. The 1950s was the decade that saw the highest number of country houses demolished – many as a result of wartime requisition and dereliction.

It was arguably the most prestigious of The Dukeries’ estates and the loss of Rufford was yet another blow to the area. Clumber House had gone, Thoresby Hall almost suffered a similar fate, and only Welbeck remained as a private residence.

Most depressing is that there are people today who have never heard of Rufford, and those that have, see it as a ruin inside a park. What greater insult can there be to such a distinguished past?

Special thanks for information provided by Matthew Kempson

Rufford Abbey,

Ollerton, Nottinghamshire, NG22 9DF