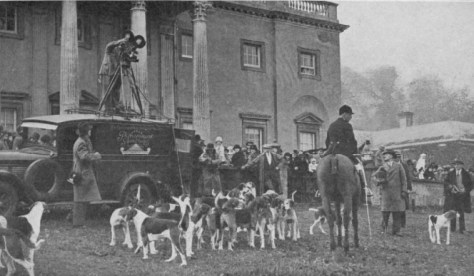

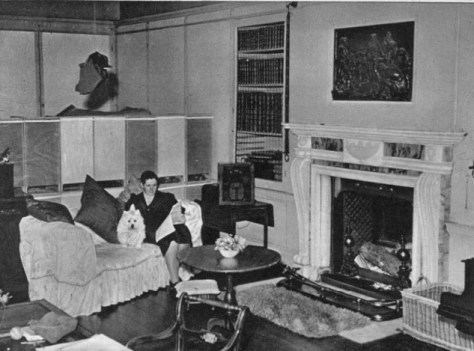

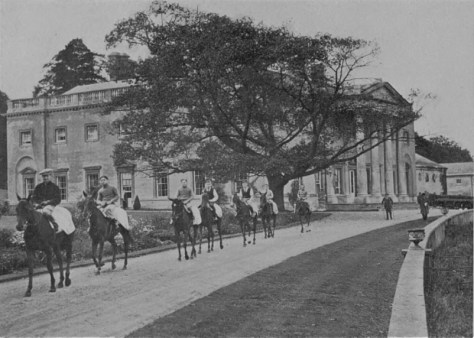

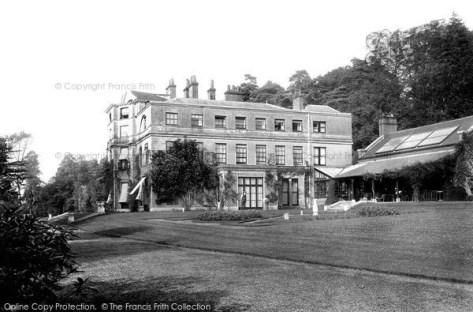

These shocking images from the late 1940s showed Moor Park, Farnham, in a perilous state of repair. The fate of Moor Park was uncertain. Occupied by Canadian troops during the war, it was out of repair, and in 1948 its property developer owner had applied to the local council for a demolition order. The Farnham Urban District Council applied to the Ministry of Town and Country Planning to have it listed as a monument of special architectural or historic interest under Section 30 of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. This gave it a two-month breathing space in which it was hoped to find some use for Moor Park, which would have ensured its preservation (it was eventually listed in 1950).

Sir Harry Brittain, in a letter to The Times, had been campaigning for its preservation.

Sir Harry wrote: “May I through your columns make an appeal for Moor Park, a historic building of far more than local interest? It lies in a beautiful setting near Farnham, facing Waverley Abbey across the River Wey. To this house Sir William Temple, statesman and man of letters, and his lady (Dorothy Osborne) came in 1684 to spend 15 years of their married life, the remaining 15 being taken up in embassies abroad. Temple called the house Moor Park after the Hertfordshire place belonging to his cousin Franklin.

“Jonathan Swift joined Sir William Temple as his secretary in 1684 and lived with him for four years. After a sojourn in Ireland he returned and remained until the death of Sir William, whose last instructions were that his heart should be buried under the sundial in the gardens he had laid out. It was in this very house that Swift wrote his first book, ‘The Tale of the Tub’, followed by ‘The Battle of the Books’. It was here that he met Esther Johnson – later immortalised in his famous ‘Journey to Stella’. The house was stuccoed in Regency times, and certain rooms on the south side centre block rebuilt in 1733. I am, however, assured by a well-known architect that nine-tenths of Moor Park is actually the house Sir William Temple knew. Many notable people stayed there, including King William III, Addison and Steele.

“Moor Park was badly treated by troops during the war and is somewhat out of repair, and the owners have applied for a demolition order. It is indeed to be hoped that this order may be averted before it is too late. I am assured that the local authority and everyone concerned are anxious that if possible this old house, with its unique associations, should be preserved for the nation. The capital involved is not large. All that is required is to find some use for Moor Park, either divided or as a whole.

“All who know it will agree that this beautiful valley, watered by the River Wey, is as fair a landscape as one could wish to see. When in addition, it holds not only the remains of England’s first Cistercian abbey, but across the stream an old home filled with literary and historical memories, as is Moor Park, every effort should be made to keep unbroken this special link with the past.” ¹

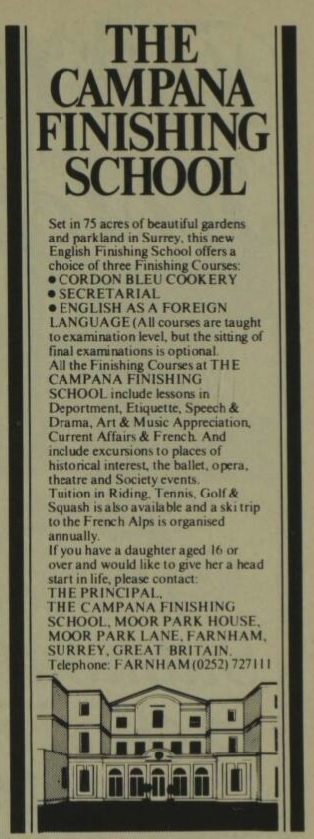

It wasn’t until the following year that a use was found for Moor Park. It was to become the first in a chain of colleges for adult Christian education, under supervision of Canon R.E. Parsons, formerly the Secretary of the Churches’ Committee for Religious Education among men in the forces and Canon and Prebendary of Warthill in York Minster. The Moor Park College for Adult Christian Education was supported by financial gifts, volunteer help and grants from Surrey County Council and survived a financial crisis in 1953 from which it was handed over to an educational trust. The chapel, library and spacious conference room provided accommodation for assemblies of up to 50 students. The top floor of the house was used by the Overseas Service, as offices and a college for persons about to embark on voluntary or business ventures abroad. The Christian college vacated in the late 1960s and it was used as a finishing school, a cookery school and later the Constance Spry Flower School. More recently it was converted back into residential use as 3 luxury apartments, with 8 new mews houses and 12 new apartments in the walled garden. ²

References: –

¹ Surrey Mirror (27 August 1948)

² The Sphere (10 December 1949)