Built: 1907

Architect: Sir Edward Guy Dawber

Owner: Private ownership

Country house and estate

Grade II listed

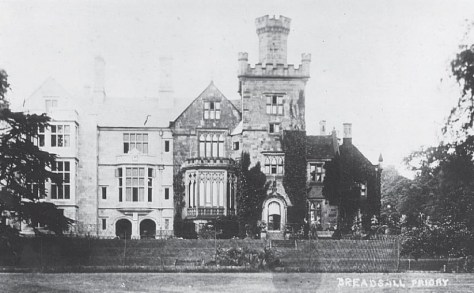

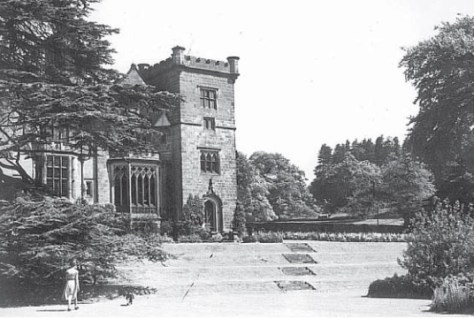

“Squared rubble stone with ashlar dressings, tall hipped stone slate roofs and prominent rubble stone stacks with ashlar quoins. Two storeys and attic, late C17 style with symmetrical garden front, asymmetrical entrance front and L-plan service court.” (Historic England)

“The selection of an appropriate local stone – taken mostly from old walls about the estate; the exceptionally suitable roofing – old stone slate – also obtained in the vicinity; and the utilisation – fused into the one design – of motives easily separated under the heads of ‘Classic’ and ‘Gothic,’ are all representative of the modern type of residence design in England.” (The Architectural Review 1907)

By comparison to other featured houses, Conkwell Grange, at Limpley Stoke, near Bath, is relatively new. Nevertheless, this Edwardian property, built 109 years ago, has an incredible amount of history attached to it.

Built from the proceeds of Yorkshire wool it suffered at the hands of the Russian Revolution. It was almost destroyed by fire in the 1920s and then we have the puzzling story of the spinster who bought Conkwell Grange and drove around in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. This is not to mention the Royal Navy Commander who was a failed fruit-grower and the civil servant who shaped the future of one of the world’s busiest airports. Throw in a few Arab racehorses and Conkwell Grange has more to tell than many of its older and grander neighbours.

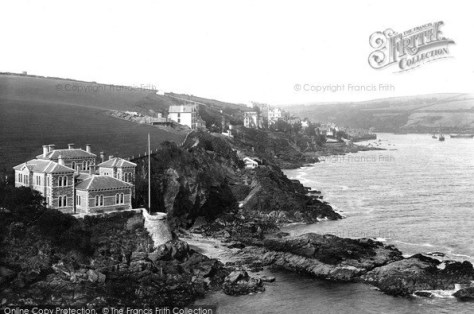

Conkley Grange, a neo-baroque house, has far-reaching views towards the Avon Valley and Salisbury Plain. The Grade II listed mansion was built in 1907 for James Thornton to a design by the renowned country house architect, Sir Edward Guy Dawber (1861-1938) at an estimated cost of £25-30,000.

Dawber was the president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) between 1925 and 1927. His work consisted mainly of stone-built country houses in the Cotswolds vernacular tradition. Houses designed by him include Nether Swell Manor (Gloucestershire), Eyford Park (Gloucestershire) and Bowling Green (Dorset).

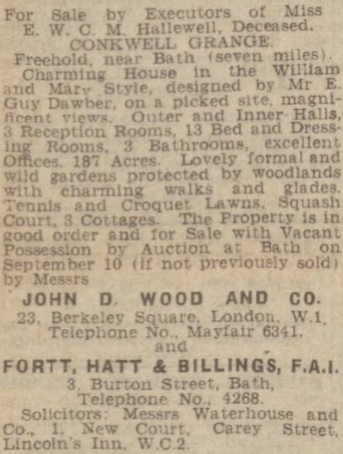

Conkwell Grange was described as a ‘modern William and Mary-style residence’ with reception rooms, 13 bed and dressing rooms, 3 bathrooms and a squash court.

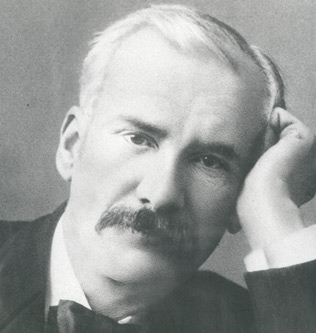

James Thornton (1865-1939)

James Thornton was the son-in-law of Sir Charles Parry Hobhouse, of Monkton Farleigh, having married Miss Lilian Hobhouse in 1900. Prior to building Conkwell Grange the couple lived at the Priory, at Beech Hill, in Reading.

Thornton was an alderman for Wiltshire County Council and Chairman of the County Education Committee. He became a magistrate for Wiltshire and Berkshire, and contested North-West Wiltshire as a Liberal in 1895 and 1900. He strengthened his political ties by acting as President of the West Wiltshire Liberal Association. Together with Harry Plunkett Greene he also started the Wiltshire Music Festival and became President of the Bath Orpheus Glee Society.

His move to Conkwell Grange courted controversy almost immediately. Thornton, wanting privacy for his new home, closed access to the historic Conkwell Woods which spread across the estate. These woodland walks had been used by locals for generations and the erection of barriers didn’t make Thornton a popular man. The obstructions were demolished by frustrated walkers and a crusade was mounted by the Bath Socialist group who alleged interference with public rights of way.¹ The dispute eventually ended up at Bristol Assizes and Thornton was ordered to take down the barriers.

Thornton might have thought his new family home, a prestigious one at that, the beginning of a new adventure. However, the clashes with locals over Conkwell Woods were nothing compared to what lay ahead.

His immediate family, with strong ties to the Yorkshire woollen mills, had made their fortune in Russia where his father and brother spent most of their lives. As a result James travelled regularly throughout Europe living off his own personal wealth.

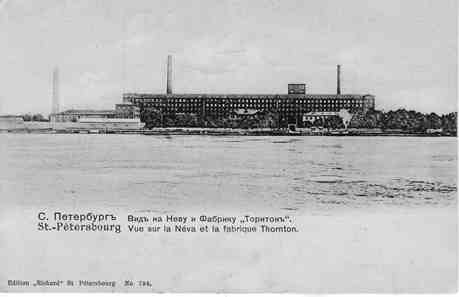

At the beginning of the 20th century the Thornton family owned cloth mills near St Petersburg proudly supplying the Russian Imperial Court . This allowed the Thornton’s to accumulate significant wealth, money which paid for the construction of Conkwell Grange, but the events of 1917 had devastating consequences.

The Russian Revolution focused around Saint Petersburg, then capital of Russia. In March 1917 members of the Imperial parliament assumed control of the country, forming the Russian Provisional Government, resulting in the collapse of the Russian Empire and the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II. The aftermath was chaotic with frequent mutinies, protests and many strikes across the country.

Havoc was wrought on the Thornton properties and the cloth mills were smashed by angry dissidents. Production stopped and the family business collapsed with James Thornton reported to have lost nearly half a million pounds.²

While events in Russia raged out of control, life continued quietly in the peace of the Wiltshire countryside. The gardens at Conkwell Grange were being carefully attended by David Lewis Bolwell, a Countrycompetent gardener, who had worked for Thornton’s father-in-law, Sir Charles Hobhouse, at Monkton Farleigh. Prior to their move he had been the gardener for Thornton at the Priory before moving in 1906 to oversee the layout of the new Conkwell Grange gardens. If anyone could speak about the secrets of the house then Bolwell was the man to do it. His love affair lasted 37 years and, rather fittingly, he collapsed and died in the gardens in 1943.

James Thornton’s stay at the house was almost at an end. In 1922, five years after the collapse of the family business, he sold up and moved to a smaller property, Turleigh Combe, at nearby Winsley.

He sold Turleigh Combe in the late 1930s looking to buy another property in the area. The search was unsuccessful and he ended up staying at Pratt’s Hotel in Bath. He died in his sleep, aged 74, in 1939. Following his death he left gross estate worth £23,578, with net personalty £22,742.³

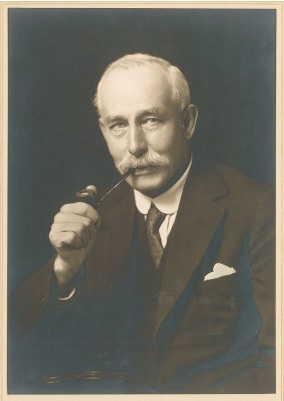

George Pollard Armitage (1867-1952)

When James Thornton left Conkwell Grange in 1922 it is possible he negotiated the sale to a friend and business contact. It may have been relief to a man who had lost half a million pounds and the man who offered a helping hand was George Pollard Armitage.

George was the only son of Joseph Armitage and Julia Francis, the daughter of George Thomas Pollard of Stannary Hall, in Yorkshire and Ashfield in Cheltenham. He was educated at Harrow and Jesus College, Cambridge.

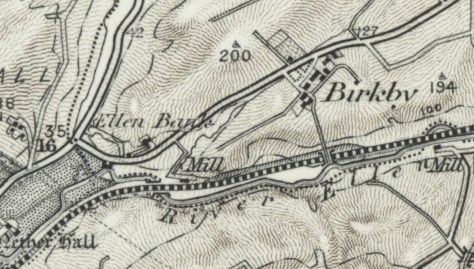

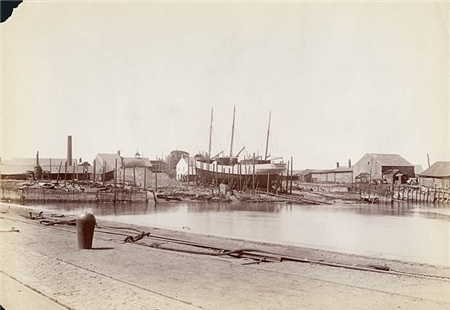

Like the Thornton’s, the Armitage family were wealthy woollen manufacturers from Yorkshire. George’s grandfather, also Joseph, had built his first woollen mill in 1822 at Milnsbridge, two miles west of Huddersfield. In the 1840s, he handed over control of the thriving business to his sons who renamed it Armitage Bros. The company prospered during the industrial revolution and with it came riches to match.

George’s own prosperity came about in 1898 when he inherited Milnsbridge House, a country mansion, and the lease of Storthes Hall, at Kirkburton, quickly selling the freehold of the latter to the county council.

He later became a J.P. for the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1902 and married Coralie Eugenie, youngest daughter of Rev. Chastel de Boinville, the vicar of Burton in Westmoreland, in 1912.

By this time the woollen industry was not such a viable business after all. The boom years had gone and the First World War caused inevitable disruption to the industry. It would be some years before the market collapsed altogether but these were ominous times for George Armitage.

He also faced a dilemma over what to do with Milnsbridge House. When built, around 1748, the magnificent house had been in idyllic rural surroundings. Over time the industries of Huddersfield had advanced and now threatened to surround Milnsbridge. About 1919-20 George decided to sell and enjoy old age in a more suitable environment. On hindsight, his prognosis was quite correct. Armitage Bros ceased trading in 1930 while Milnsbridge House survives in an industrialised suburb of Huddersfield. For more details about Milnsbridge House please refer to an earlier post at Rudding Park.

With proceeds from the sale of Milnsbridge House George Pollard Armitage moved to Conkwell Grange in 1922.⁴

He spent his time at Conkwell Grange developing the estate for agricultural use and extended it to about 400 acres.

His stay was not without drama and the house was nearly lost on Christmas morning in 1925. A fire started in the day nursery and a call made to the fire brigade to attend. By the time they arrived at this remote location the fire had been brought under control by hard-working servants including, no doubt, the gardener David Bolwell. The blaze caused £400 worth of damage but Conkwell Grange survived owing to the nature of the walls and ceiling, which were lined, rather alarmingly, with asbestos. Fortunately the main damage was confined to the one room but the house was smoke-logged.

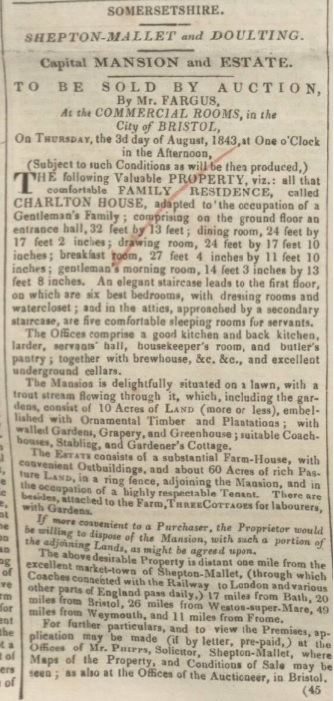

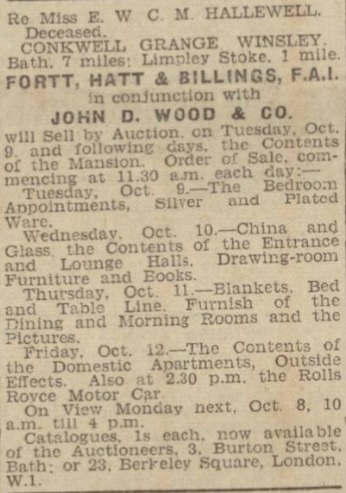

In 1933, with the collapse of Armitage Bros still rankling, George decided to put the Conkwell Grange estate on the market. He had his eyes on a nearby property, Hunters Leaze, and so appointed Thake and Paginton, of Newbury, and Fortt, Hatt and Billings, of Bath, to negotiate a sale. The land was divided and Conkwell Grange, along with about 125 acres, was sold to Miss Ethel Hallewell.

George Pollard Armitage moved to Hunters Leaze and died in 1952 leaving estate worth £14,440.

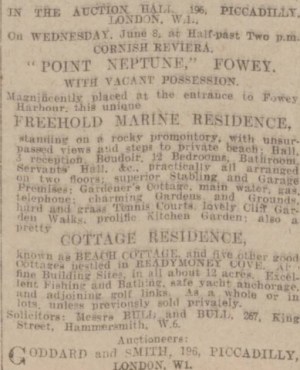

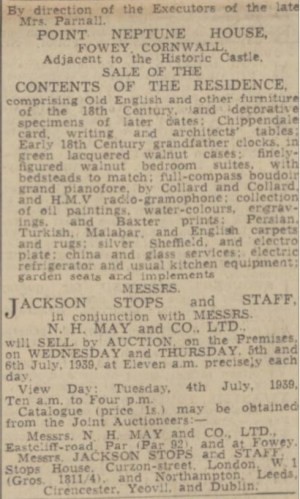

Ethel Winifred Catherine Hallewell (1864-1945)

Ethel Hallewell was described in the press as ‘a lady who frequently visited Bath and chose to make her home in one of the choicest country districts that surround the city’.

The 1911 census reports that she was living by private means but as to how she acquired such wealth remains a mystery. For several years Ethel Hallewell had been a regular guest at the Pulteney Hotel in Bath and was most likely keeping an eye out for a suitable country house to live.

She was born in 1864 in Cape Town, the daughter of Charles James Maynard Hallewell and Amelia Catherine Barber, who had moved to South Africa.

Charles Maynard was a Captain in the Cape Mounted Rifles but the birth of Ethel prompted their return to England. He became a Lieutenant with the 19th (1st Yorkshire North Riding – Princess of Wales’s Own) Regiment but the family lived at Axminster in Devon.

Charles retired from military service in 1866 and a year later a son, Frank Maynard Hallewell, was born. In later years Charles (and his second wife Catherine Sophia Wilde) lived at Bryn Hyfryd, Conway, before returning to Devon at Deepdene, in Bathampton.

Charles died in 1919 leaving just £917 in his will. A lot of money then, but in comparison, when Ethel died in 1945 she left estate worth £144,649. She remained a spinster and, with no husband earning an income and no obvious benefactor, her finances remain a matter of speculation.

Maybe the answer to this conundrum lay thousands of miles away in South Africa? There were strong family connections and her brother, Frank, had followed in their father’s footsteps and joined the Cape Mounted Rifles. He died in 1937, aged 70, in a car accident at Vereeniging in the Transvaal. Sadly, he was also unmarried and without issue.

When Ethel died in 1945 she made provision for several charities, all of whom received £500 each.

The Child Emigration Society, founded in 1911 and better known as the Fairbridge Society, was dedicated solely to child migration, sending children to its farm schools in Australia and British Columbia and to a college in Southern Rhodesia.⁵ In addition Ethel made further provision of £500 to support the Fairbridge Homes.

The reason for Ethel’s support is speculative but no doubt she believed she was bettering the lives of impoverished children from Britain’s slums. Far from improving lives, the scheme was eventually exposed with stories of cruelty, hardship and of families torn apart.

Two further charities benefited from her will. These were the National Library for the Blind and the Royal Blind Pension Society (pensions for the blind poor). Dare we speculate that Edith was herself blind, perhaps prompting her parent’s hasty departure from South Africa after she was born? Or was it simply a case of her being a caring and wealthy individual?

Another bequest of £250 was made to the Home of St Giles, an Essex charity that raised money to fund a hospital designed specifically for the care and treatment of leprosy. Although, by the turn of the 20th century the disease had long been eradicated in Britain, this hospital provided for the few people who had caught it abroad.⁶

Ethel also made provision for her chauffeur, Sidney J. Waldron, who had paraded her around in a Rolls-Royce, and received the handsome sum of £600. However, her greatest bequest went to a relation, Commander Edmund G Hallewell, retired of the Royal Navy, who received £12,000.

It was he who decided to put Conkwell Grange up for sale and, in 1946, sold it to another Royal Navy officer, Commander Wardell-Yerburgh.

Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh (1891-1953)

In the course of researching these articles there often comes a time when something doesn’t quite ring true about a person. All too often history tends to be kind but something about Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh suggested ‘scoundrel’.

When I originally wrote this piece I invited comment from anyone who might have been able to put the record straight. I was subsequently delighted to hear from his son, Richard Wardell-Yerburgh, who said he was “profoundly amused by the description of him as a ‘scoundrel’ because it precisely reflects my own view.”

However, Arthur’s upbringing had been impeccable, being the son of Reverend Oswald Pryor Wardell-Yerburgh, Vicar and later Canon of Tewkesbury, and Edith Wardell Potts. Arthur lived with them until his early twenties at the Abbey House in Tewkesbury. This wealthy family were descended from the Rev. Richard Yerburgh, the vicar of Sleaford in Lincolnshire.

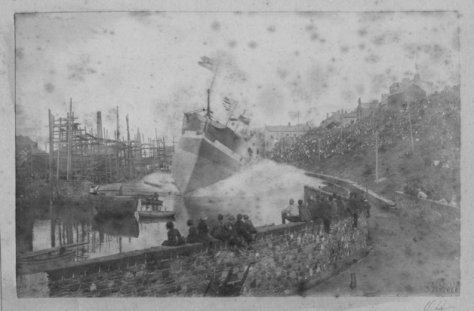

Arthur joined the Royal Navy in 1904 training at Royal Naval College, Osborne, on the Isle of Wight, and at Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in Devon. He joined active service in 1909 serving as a Midshipman on HMS Agamemnon and later HMS Indefatigable. In 1914 he was promoted to Sub-Lieutenant and given command of submarines. He was decorated with the award of the Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) in 1918 for operations off the Belgian coast..

The following extract is taken from The Dover Patrol 1915-17, by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, and refers to his preparations for a “Great Landing” on the Belgian Coast, a plan which was eventually postponed but which was at least reflected in the subsequent raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge. It also mentions Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh and the circumstances into achieving the D.S.C.:

‘It was necessary that our survey should be accurate to within six inches. A submarine (known as C30) was, therefore, sent to submerge off Nieuport, to lie on the bottom, and to register the height of the water above her hull continuously for twenty-four hours by reading the depth gauge. The rise and fall and the tide curve at this spot was thus obtained at springs, neaps and intermediate tides.

This information was obtained by Lieutenant Wardell-Yerburgh. It was a weird experience for a submarine to steal up and submerge right under the guns of the enemy’s coast defence, always with the off-chance that in her journey to the bottom she might settle down on a mine. Also as the submarine was a C Boat, and not large, and as she had to remain submerged for twenty-four hours, she was apt to get stuffy. The number of crew was therefore reduced to a minimum.’

Arthur retired from the Royal Navy in 1921 and married Enid Mary Florence Till, the daughter of John Till of Kemerton Court. In December 1921 John Till died while hunting after suffering a seizure and falling off his horse. He left gross estate worth £35,334. Kemerton Court was left for his wife, Florence, and the residue of his property was placed in trust for his three daughters, including Enid, and presumably Arthur.

He re-joined the Royal Navy in 1922, probably as a commissioned officer, and was awarded the rank of Lieutenant-Commander. However, the period between two World Wars saw a decline in the number of Royal Navy ships and Arthur probably never saw active service again. If this is the case, then considering he always referred to himself as Commander Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh, then never has such a title been so ill-used

Without a ship to command, but a title nevertheless, Arthur and Enid moved to Wesmacott, near Tewkesbury. It was here that he hatched plans for a fruit farming business at Bredon. While at Wesmacott they had their only child, John Gerald Oswald Wardell-Yerburgh, born in 1925.

There was a difference between the sea and fruit farming and Arthur realised he had made a mistake. The business wasn’t a success and his relationship with Enid was strained to say the least. Just how much money was lost in the enterprise is unknown but, in 1926, they sold up and went to live with Enid’s mother at Kemerton Court.

If this was an attempt to reconcile their differences within a stable family environment then it proved ill-advised. More likely the move was the result of financial hardship caused by Arthur’s failed business venture. Enid, frustrated by Arthur’s inability to gain meaningful employment and no doubt encouraged by her mother, became increasingly disenchanted. By 1929 the couple were living apart with Arthur staying at Westbourne Terrace in Paddington.

In January 1931 he and Enid were divorced on the grounds that Arthur had committed ‘misconduct’ at a London hotel.⁷ Arthur didn’t defend the suit and Enid was granted a divorce, with costs and custody of their child.

We know that many divorces were ‘staged’ affairs. The law at this time required one of the parties to be caught and witnessed in liaison with another person. In circumstances where a relationship had broken down it was not unknown for such affairs to be instigated by both parties. In this case the witnesses were John Russell, a private inquiry agent, and Thomas Hawkins, a waiter at the Hotel Central in Marylebone, where the wrongdoing was alleged to have taken place.

Richard Wardell-Yerburgh believes that Enid Till was disgracefully treated as was his half-brother, John.

“I believe the principle reason for the trouble was that Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh was in the habit of borrowing from Enid’s friends and relatives. Unfortunately, it appears he was not in the habit of re-paying these loans. Arthur never spoke or wrote to his son, John, from the day of the divorce until the day that he died. I only learned of John’s existence by accident.”

Enid might have had moral ground to obtain a divorce and we will never know whether this woman was a ‘put-up’ affair or someone directly involved with Arthur. That someone might have been Marion Georgina Cooper, from Paddington, because, with the ink barely dry on the ‘decree nisi’, she was married to Arthur in September 1931 (although Richard Wardell-Yerburgh believes this was in 1933).

With changes in the air it was also time for Arthur to call time on the Royal Navy and he officially retired from the service.

This time the marriage appeared more compatible and lasted the course. The couple settled at Worton Grange, near Devizes, where they had a son, Richard Geoffrey Robert Wardell-Yerburgh (b. 1935), subject of welcome correspondence in this post.

“The marriage between my mother, Marion Cooper, did nothing to stabilise Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh’s financial position. She was penniless, the daughter of a London milkman, and had determined that she would somehow get herself out of Paddington. She lived in the area of Paddington either in, or adjacent to, Westbourne Terrace (where Arthur had been living in 1929).

“Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh was apparently well-healed and Marion grasped the opportunity. That she had made the wrong decision only dawned to her as the paucity of Arthur’s finances became apparent.”

The move to Conkwell Grange followed a succession of deaths within Arthur’s close family. In April 1941 his sister, Hilda, died when a fish bone caught in her throat while dining at Littlewood House, near Frampton. Three months later his mother died leaving an estate worth £14,498. Arthur received £2,200 and shared the residue of her property with his younger brother, Geoffrey Basset Wardell-Yerburgh. Geoffrey didn’t live long enough to enjoy his windfall and died in 1944.

“Arthur earned not one penny from the Royal Navy after he retired until the day he died,” says Richard Wardell-Yerburgh. “Everything came from his mother, Edith Wardell-Yerburgh, who has been described as being ‘As rich as a Croesus’ – including settling debts from two bankruptcies – the fruit farm and a business called the Light Car Company.

“In 1931 she paid a settlement figure into a Trust for the support of my half-brother, following the divorce from Enid. My mother told me this was in the sum of £25,000 (in 1931/32). According to the Historic Inflation Calculator (HIC), this equates to £1,472,650 at today’s rates. When she died, I understand my father actually inherited £167,000 after deduction of the monies paid out for his debts. According to the HIC this amounts to £8,419,963 at 2016 values.”

Arthur and Marion moved to Conkwell Grange in 1946. The house, with its stately grandeur and a Rolls-Royce to match, suited him in his retirement years. However, they were to stay just 5 years before ‘down-sizing’ and re-locating to Hall Farm, at Thickwood, in 1951. This was where Arthur died in 1953, at the relatively young age of 61. He left effects to the value of £21,493. His wife, Marion, died in 1984.

The last word goes to Astra Towning (nee Wardell-Yerburgh), the daughter of Richard Wardell-Yerburgh:

“My grandfather was a very handsome young naval officer and he and my grandmother (Marion) made a very glamorous couple. Marion ended up in a small house stuffed with glorious, if unloved, furniture, antiques, jewellery and furs. Most of this went in a series of burglaries, including Arthur’s ceremonial naval swords. We have a journal from his time in the navy. This book is huge and beautifully presented – lovely writing, glorious pictures of ladies he knew in various ports, and wonderfully detailed technical drawings.”

Philip Eric Millbourn (1902-1982)

Conkwell Grange was bought by Philip Eric Milbourn (1902-1982), a Yorkshireman, whose reputation has diminished with history. He was the Honorary Advisor on Shipping in Port to the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation.

Here was a man, from humble beginnings, who shunned publicity and chose to get on with his job while, at the same time, acquiring a personal fortune. For this reason his name is almost ‘air-brushed’ from the archives and virtually unknown today.

Eric, as he liked to be called, married Ethel Marjorie Sennett, the only daughter of Joseph Ernest Sennett, of Kingswood Grange, Reigate, in 1931. His job required a town house and for many years they lived at 41 Parkside in Knightsbridge, as well as living at a cottage on the Kingswood Grange estate.

Their move to Conkwell Grange corresponded with a glorious decade for Eric. In 1950 he had been awarded the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George (C.M.G.) and was knighted five years later. However, his greatest accomplishment came in in circumstances not dissimilar from today. Faced with escalating passenger numbers at London (Heathrow) Airport he was asked to head a committee to determine how the problem might be resolved. With meticulous foresight his findings were presented in the Millbourn Report of August 1957.

His contribution shaped the Heathrow Airport we know today. In the report he recommended that all Heathrow’s terminals be located in one central area. With this he suggested the construction of a new long-haul terminal (now Terminal 3) and a short-haul terminal (which became Terminal 1). In addition, the report called for the expansion of Gatwick Airport. The total cost of these proposals was an estimated £17 million to handle the 12 million passengers anticipated by 1970.

The Millbourn Report was the zenith of a career that demanded Eric travel the world advising on transport problems. It also made him a very wealthy man and, on his death in 1982, he left estate worth £1,779,975. Lady Millbourn died the year after and Conkwell Grange was once again put on the market.

The Fosler family and the racehorse stud

The house was eventually purchased by the Fosler family in 1985 who made the estate the centre of a stud farm and racing stables. Today it is an estate of 300 acres mostly devoted to woodland and horses. A 100 box complex of equestrian buildings have been used as a thoroughbred stud and, at the turn of this century, was used for the breeding and training of Arab racehorses. More recently it has been the home to the Neil Mulholland stables.

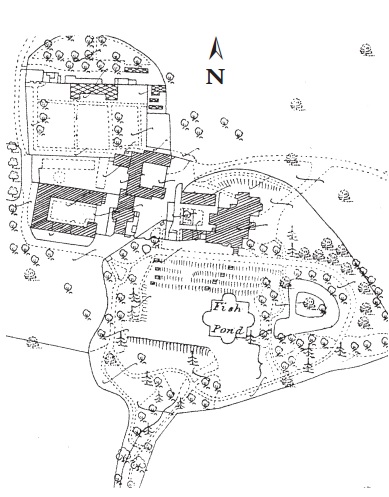

Nowadays, Conkwell Grange is approached through impressive stone pillars and a pair of lodge cottages leading into a magnificent mature beech avenue. Surrounded by mature plants, accessed through its own gated drive, the property sits in a private position within maintained gardens and grounds amongst the pastureland.

In 2016 Conkwell Grange was brought to the market with a guide price of £5.9 million. Today’s accommodation is on three floors, including five reception rooms, 10 bedrooms and five bathrooms. In addition there are two lodge cottages, six further cottages and four staff flats providing secondary accommodation, with 128 acres of managed woodland to the west of the estate creating shelter and privacy for the main house.

References:-

¹Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser (22 Jun 1907)

²Gloucestershire Echo (1 Apr 1939)

³Western Daily Press (3 Jun 1939)

⁴Landed families of Britain and Ireland (Nicholas Kingsley) http://landedfamilies.blogspot.co.uk/2015/07/177-armitage-of-high-royd-and.html

⁵ Child migration: philanthropy, the state and the empire – Stephen Constantine, Lancaster University (History in Focus)

⁶“Caring for Hansen’s Disease – The Hospital & Homes of St. Giles 1914-2005” by Nicholas Best

⁷Cheltenham Chronicle (17 Jan 1931)

I am indebted to Richard Wardell-Yerburgh and Astra Towning for providing fascinating details about the colourful Arthur Wardell-Yerburgh.

Notes:-

In 1937 James Thornton was involved in an unusual incident at Bradford-on-Avon Police Court. While presiding as a magistrate he left the bench and entered the witness-box to answer a charge for failing to stop at a halt sign. Thornton, who pleaded guilty, said he had a lady passenger in the car at the time who attracted his attention talking about the beauty of some trees. In future, he said, he would fix a notice on his windscreen requesting passengers not to talk to the driver while they were approaching halt signs. He was fined £1, which he paid, and then returned to the bench to administer justice elsewhere. (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette – 18 Sep 1937)

Conkwell Grange,

Limpley Stoke, Bath, Wiltshire, BA2 7FD